Abstract

Case Report: Inflammatory Cerebral Amyloid Angiopathy - Recognizing a Treatable Form of Cerebral Vasculitis

Pages: 1-6

Category: Short Report

Published Date: 12-12-2025

Garrett Harris1, Chimaobi Ochulo2, and Arjun Athreya1

Author Affiliation:

1 Division of Neurology at Lexington Medical Center, USA

2 American University of the Caribbean-School of Medicine, USA

∗ Correspondence: Garrett Harris, Email: garrettEharris@gmail.com

Keywords:

Inflammatory Cerebral Amyloid Angiopathy, Cerebral Vasculitis, Boston Criteria 2.0, Neuroimmunology, Cognitive Decline, Immunosuppressive Therapy

Abstract:

Objective: To highlight the diagnostic and therapeutic importance of recognizing inflammatory cerebral amyloid angiopathy (iCAA) presenting with atypical cognitive decline and evolving neuroimaging findings.

Background: Cerebral amyloid angiopathy (CAA) is an age-associated disease characterized by gradual deposition of beta-amyloid within the walls of cortical and leptomeningeal vessels. The inflammatory variant (iCAA) can cause subacute encephalopathy, seizures, and headaches with asymmetric white matter edema that can be steroid responsive. Diagnostic delays can occur due to the slow evolution of disease and overlap with more prevalent pathologies.

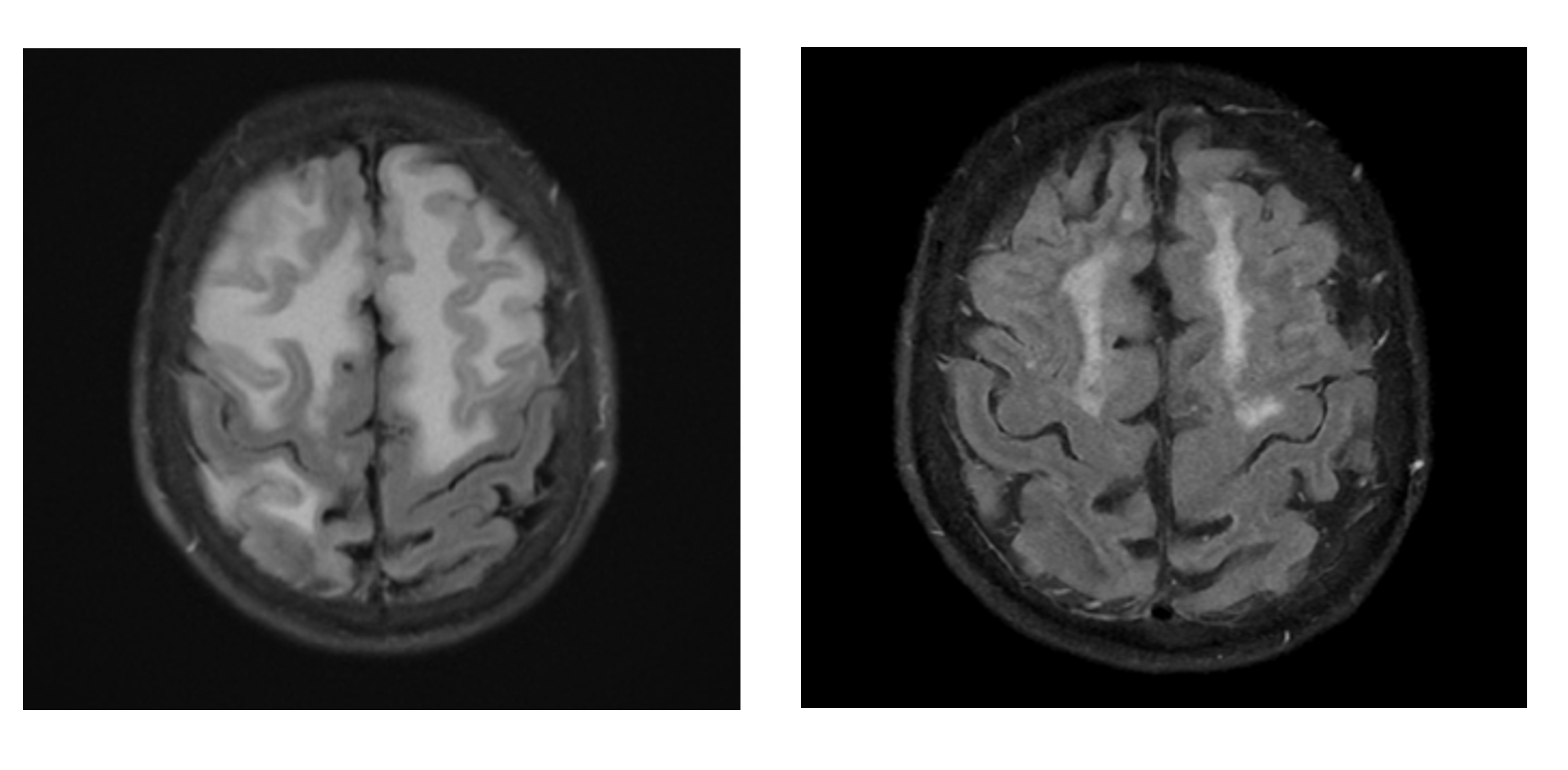

Results: An 84-year-old woman initially presented with progressive aphasia. Brain MRI revealed lobar hemorrhage, T2 FLAIR white matter changes, and widespread cortical microbleeds. She was diagnosed with primary intracerebral hemorrhage but was lost to follow-up. Several years later, she returned with acute encephalopathy, worsening cognitive function, and radiographic changes that were inconsistent with previous explanations. The extensive workup for infectious and neoplastic conditions was unremarkable. Repeat imaging revealed persistent cortical microbleeds alongside new vasogenic edema—now fulfilling Boston Criteria 2.0 for probable CAA, with rising concern for an inflammatory variant. A brain biopsy was considered but deferred. High-dose IV methylprednisolone was initiated empirically, followed by an oral prednisone taper. Within weeks, she showed rapid clinical recovery, and follow-up MRI confirmed resolution of vasogenic edema with no new hemorrhages. Two months later, she regained baseline cognitive function and was independently performing daily tasks.

Conclusions: This case illustrates how evolving radiologic patterns, when paired with unexplained clinical decline, can unmask a treatable diagnosis. iCAA mimics alternate pathologies but responds dramatically to immunosuppression. Delay in recognition can cost precious recovery time. Early identification, grounded in evolving imaging and clinical suspicion, can lead to cognitive improvement. Clinicians must remain vigilant to evolving MRI patterns and unexplained cognitive changes, particularly when prior diagnoses fail to account for clinical reality.